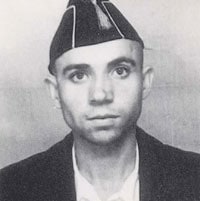

Miguel Hernández Gilabert (also known as Miguel Hernández) was a leading 20th century Spanish poet and playwright.

Born in Orihuela, Spain to a family of seven children and given little formal education, Hernández published his first book of poetry at 23, and gained considerable fame before his death. His 1933 book, Perito en Lunas (“Expert in Moon Matters”) was marked by his creative use of metaphors, and is one of his most famous works.

He spent his childhood as a goatherd, and was, for the most part, self-taught, although he did receive basic education in state schools and with the Jesuits. He was introduced to literature by his friend, Ramon Sije. As a youth, he greatly admired the Spanish poet Luis de Góngora, who was an influence in Hernández's early works. As many Spanish poets of his time, he was deeply influenced by the European vanguards, remarkably by Surrealism. However, although he used novel images and concepts in his verses, he never abandoned classical, popular rhythms and rhymes. Two of his most famous poems were inspired by the death of his friends Ignacio Sánchez Mejías and Ramon Sijé.

During the Spanish Civil War he campaigned in favor of the Republic, writing poetry and addressing the troops deployed to the front. Hernández was arrested multiple times after the war for his anti-fascist sympathies, and was eventually sentenced to death. His death sentence, however, was commuted for a prison term of 30 years, leading him to live in multiple jails under extraordinarily harsh conditions until eventually succumbing to tuberculosis in 1942.

While in jail, Hernández produced an extraordinary amount of poetry, much of it in the form of simple songs, which he collected in his papers and sent to his wife and others. These poems are now known as his “Cancionero y romancero de ausencia” (“Songs and Ballads of Absence”). In these works, Hernández writes not only of the tragedy of the Spanish Civil War and his own incarceration, but also of the death of an infant son and the struggle of his wife and another son to survive in poverty. The intensity and simplicity of the poems, combined with his extraordinary situation, give them remarkable power.

Perhaps the best known of Hernández’s works is a poem called "Nanas de Cebolla" ("Onion Lullaby"), a poem in which Hernández replies to a letter from his wife in which she told him that she was surviving on bread and onions. In the poem, Hernandez envisions his son breastfeeding on his mother's onion blood (sangre de cebolla), and uses the child's laughter as a counterpoint to the mother's desperation. In this as in other poems, Hernandez turns his wife's body into a mythic symbol of desperation and hope, of regenerative power desperately needed in a broken Spain.

Biography reviewed by the Fundación Cultural Miguel Hernández